Beyond 5G: what would 6G look like — and do we need it?

In 2019, engineers from telecommunication companies around the world sat in a large conference hall in Geneva, trying to conceptualise how people will live and communicate in a decade’s time.

They were gathered at the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), a UN specialist agency, attempting to formulate the basis for what the sixth generation of network technology would look like — even before the fifth generation had fully proved its value.

“It’s about identifying that gap between what consumers want and what a network can do,” says Magnus Frodigh, head of Ericsson’s research division. “We are . . . guessing what these gaps will be.”

Unlike some of the more organic technological innovations of the past half-century, network evolution has historically been segmented into 10-year chunks, with each resulting in a new “generation”.

The 1980s brought 1G, a voice-only analogue service; 2G in the 1990s offered short message service (SMS) and picture messaging; 3G in the noughties delivered more data, video calling, and a mobile internet; 4G, at the end of that decade, was 500 times faster and enabled mobile television, video conferencing and real-time apps.

Then, a few years ago, 5G arrived to much bluster. It promised low latency (limited delays) and the ability to have thousands of machines talking to each other at the same time.

Basic research into what the sixth generation might look like started even before that: as far back as 2017.

But, now that 5G is here — and some consumers still ask what real-world benefits it offers — there is a feeling among some in the telecoms industry that it might be time to move beyond the “Gs” and towards more organic change, which is less likely to lead to disappointments.

After all, some of the biggest changes that each “G” have brought have come within that generation — not from switching to the next one.

Ronny Hadani, chief scientific officer at Cohere Technologies, a spectrum software company, says: “I personally believe it’s crazy for the industry to be in a 10-year cycle, when the world is changing overnight. The cloud is updating weekly.”

Santiago Tenorio, network architecture director at Vodafone, goes further, arguing that “nobody needs 6G”.

“The industry should make 6G a no-G,” he says. “There is practically nothing left that we’re missing in a hypothetical new generation. We would be much better off improving services and applications.”

Still, despite the naysaying, momentum for 6G is building. Frodigh says there are now dozens of researchers wholly dedicated to 6G research at Ericsson.

He adds that test beds are likely to start emerging as early as 2024, with the first version of the standards — which shape the way networks around the world operate — likely to be ready by 2028.

“We will update 5G during these years but there will be a demand for even more capacity, even more features, that will get more and more difficult to add,” he says.

“Many things are a continuum, but sometimes there is a logic in breaking the evolution apart.”

What might the 6G world look like?

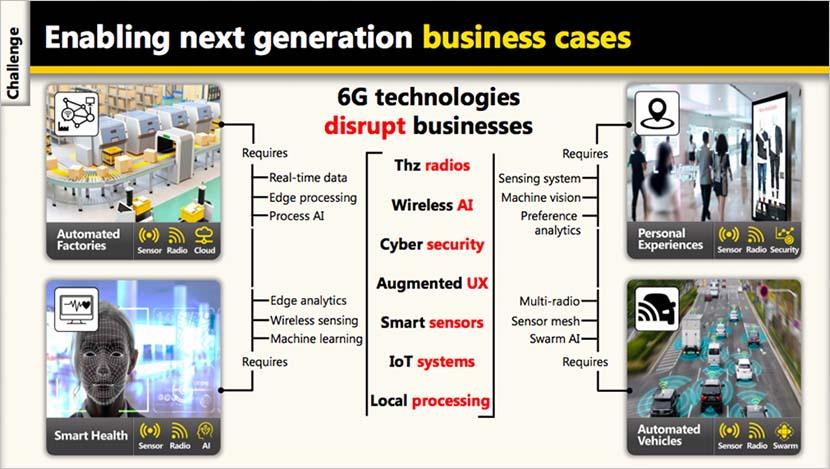

Research is in its infancy but carriers and network providers are beginning to focus their thinking around certain themes that greater speed, increased data processing, and lower latency will enable.

Some we have heard about before with the advent of 5G, including intelligent machines connected to one another and sharing data seamlessly. These interconnected machines would be hyper-intelligent, in a way that might enable the use of delivery robots and drones, and a fully functioning, highly connected “smart city”.

Others are more perplexing, though — such as Ericsson’s notion of the “Internet of Senses”, whereby people might be able to smell, feel and taste things within a digital world.

“Interacting with the network in a more immersive way — that is what 6G is likely to enable,” claims Frodigh.

A further theme is referred to as a “cyber-physical continuum”, whereby the digital world bleeds into the natural, physical world seamlessly — something that would be possible only with the almost complete eradication of latency, or processing delays.

Much of the thinking on this comes from augmented reality, and the growing frenzy aroused by the nebulous and undefined idea of a virtual world or ‘metaverse’.

Frodigh says we could get to a stage where “almost everything has a digital twin”.

This would enable network users to make real-time models of things and go back in time [within that twin world] to analyse what went wrong, or make simulations of what might happen in the future.

The network will also need to evolve to become more homogenous and have AI embedded natively within it, to make it smarter, more responsive and able to heal itself, explains Henk Koopmans, chief executive at Huawei Research and Development. “It’s about the intelligence of everything,” he says.

What do we need to do to make 6G a reality?

Frodigh argues that the best preparation that carriers can make for 6G is to keep investing and building 5G networks.

“You will have a good network, you can upgrade it and you have the customer base so you can make money on it,” he says.

Similarities in the spectrum and wave structure mean that networks can be gradually reformed without having to rip out infrastructure and start again, Frodigh adds.

But, he says, one of the big research questions for 6G is whether the network could use even higher spectrum frequencies — with propagation properties more like visible light.

This would require many more signal access points to be added to environments — for example, in residential streets — to carry the signal.

Ronnie Vasishta, senior vice-president of telecoms at Nvidia points out that sophisticated artificial intelligence will be a requirement of any network “beyond 5G” and that companies that are serious about network evolution should invest in that.

For now, though, much of the work being done to develop the next generation network is happening behind closed doors. There is, after all, a risk that the industry will lose credibility by talking about 6G before 5G has truly delivered.

- Prev

- Next